Milgram’s obedience experiments and Candid Camera

In a famous scene from the 1960s TV show Candid Camera a taxi driver watches incredulously as a car in front of him splits in half. One half makes a right turn, the other a left.

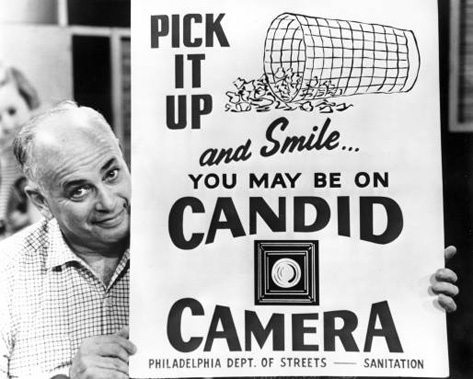

The hugely popular comedy screened on Sunday evenings from 1959 to 1967. In the show, host and creator Alan Funt secretly recorded ordinary people’s reactions to bizarre situations. Funt’s hapless but trusting victims stood open mouthed in front of a letter box that spoke to them as they passed by, or watched with dismay as a phone box flew up in the air. When their bewilderment was almost excruciating to watch, a voice would sing gaily ‘Smile! You’re on Candid Camera’ and the tension was broken.

What was striking about the show was how good-natured most people were when the hoax was revealed.

Milgram urged social scientists to admire Funt’s show

Stanley Milgram was a big fan of Candid Camera. He wrote about the similarities between social psychology and Funt’s TV show. Both, he said, creatively examined the disruption or violation of rules, captured people’s real and spontaneous reactions, and offered surprising insights into human behaviour.

Candid Camera had its roots in social psychology

What Milgram didn’t know was that the show’s creator Alan Funt worked briefly as a research assistant for psychologist Kurt Lewin. Lewin, a hugely influential social psychologist, made deception and secret surveillance a trademark of his research.

But it was Funt’s wartime experiences in radio that first gave him the idea for the show. He noticed how people let their guard down when they thought he’d stopped recording them.

Obedience to Authority owes much to Candid Camera

Milgram’s experiment, like Funt’s TV show, placed ordinary people in a bizarre situation. They arrived at Yale for an appointment to take part in an experiment about memory and learning. To their surprise, they were seated in front of a shock machine and told to give a man an electric shock each time he gave a wrong answer on a memory test.

Behind a two way mirror, a hidden audience (Milgram often invited others along, including his fiancé) watched the proceedings. All of Milgram’s subjects were recorded on audiotape, some were photographed and filmed. When the experiment was over, the subject was reunited with the ‘victim’ Candid-camera style, who laughed and joked that no harm had been done.

Milgram used a cover story, actors, hidden tape recorders, props and pretence in an effort to capture ‘real behaviour’ in his lab.

Slapstick or serious science

Milgram was sensitive to comparisons between the TV show and his obedience experiments.

Alan Elms, Milgram’s research assistant, sent Milgram a draft chapter he’d written for his upcoming book. Elms described the experimental set up in detail. He wrote about how Milgram made up fake names for the ‘learner’ and the ‘experimenter’ and how Milgram didn’t use his real name either when he came out to talk to the subjects after the experiment was over. Elms told me that Milgram read the chapter and wrote back saying, “This sounds too much like a bedroom farce. Get rid of it.” So I did.”

The suspicious never made it to the final cut

Funt estimated that between 1950 and 1985 he hoaxed and recorded one and a quarter million people. But only a portion of them – those that reflected the perfect combination of dismay, confusion and surprise – were broadcast. Funt would have left the openly suspicious, those who spoiled the joke by guessing it too early, on the cutting room floor.

Milgram too, downplayed those who saw through his experiment. He dismissed those people who said they guessed the experiment was a hoax. But unpublished papers at Yale show that many more people than Milgram let on had doubts that the experiment was real. And that many, although distressed and disturbed by what the experimenter was asking them to do, believed that Yale would never sanction an experiment in which a man was being harmed.

Milgram, Funt and reality TV

Just like the taxi that split in half only to merge again later, highly staged experiments like Milgram’s and TV stunts like those on Candid Camera have converged into a new form of reality TV. In a strange twist, experiments like Milgram’s have become a form of popular entertainment. The obedience experiments have been replicated for prime time news and reborn in game show formats, and been used in TV ads, blurring the boundaries between sadistic prank and serious science.

1 Comment

Pingback: The Holocaust and social psychology | Gina Perry