John Williams, the man who played the role of the experimenter in Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments, was much more than simply an actor. Williams’ role has been downplayed in the standard story of the obedience research. Without Williams, Milgram would never have been able to conduct the research that made him famous.

Milgram recruited Williams through an ad in the New Haven Register. John (‘Jack’) Williams had a natural authority born of his experience as a high school biology teacher. He was used to commanding attention and maintaining order. Milgram recognized that Williams was ideally suited for the part he had in mind and he offered him the job in the summer of 1961.

Milgram described Jack Williams only briefly in his articles and book about the experiments. But Milgram was far more dependent on Williams than we’ve ever been told.

Milgram trusted his staff

Milgram required that his staff keep the experiments secret. By keeping the experiments quiet, Williams and the others kept news of the research spreading in the local community, ensuring that the pool of potential subjects would remain ignorant of the experiments’ true purpose.

Williams kept details of his second job from his wife, family and friends for over ten years. Even then, he only told his son Keith about his role in the experiments when Keith was in college and likely to come across the research in his psychology textbook.

More importantly, Milgram relied on Williams to conduct the experiments in his absence. Milgram was only present at about a third of the experiments. He watched from behind a one way mirror as Williams conducted the experiment with around 240 people. Williams was left to conduct the rest – around 480 people – without Milgram.

From the moment the subject arrived to the moment they left the lab, Williams was in charge. He gave the instructions, kept notes, exhorted people to continue in the face of their stress and confusion, faced their anger and distress and debriefed them when the experiment was over.

No wonder Milgram gave him three pay rises in the nine months that they worked together. Williams’ hourly rate in August 1961 was $2 an hour, and had risen to $2.40 by the time the experiments ended in May 1962. Milgram couldn’t afford to lose him.

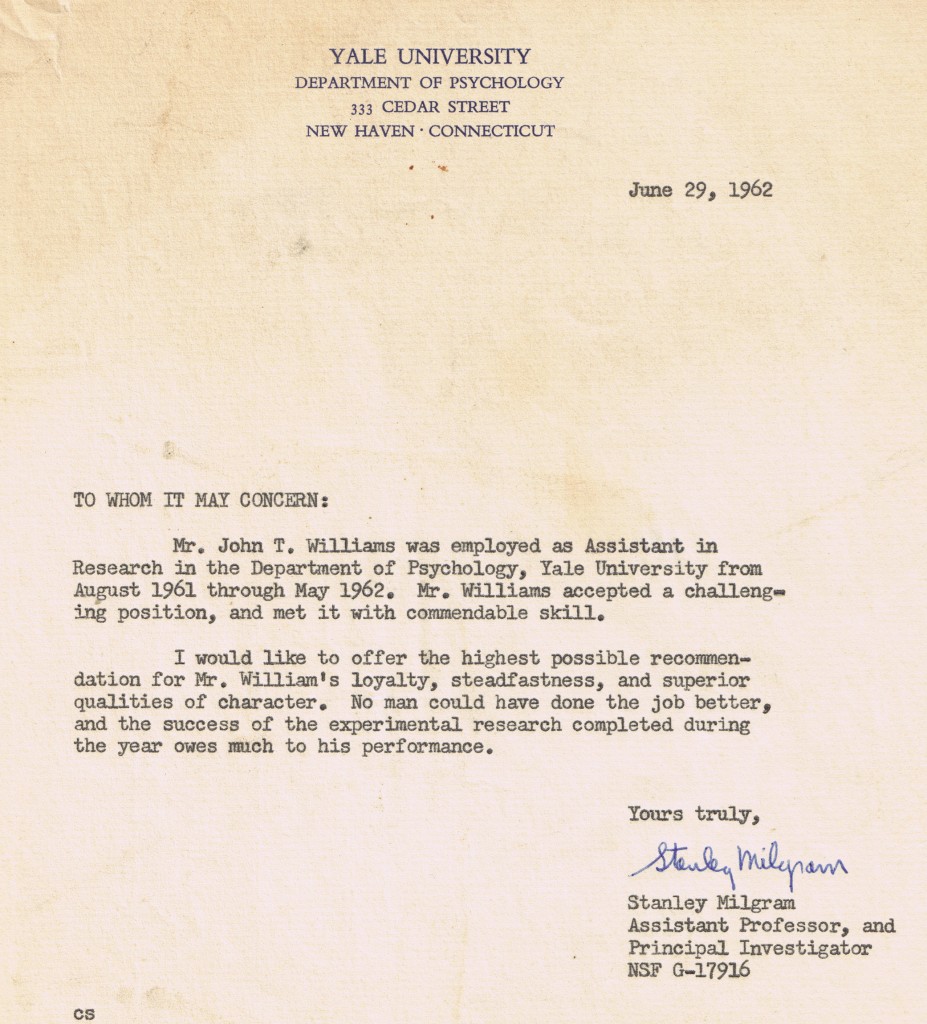

Milgram’s letter of recommendation

Keith Williams remembered that his father had kept a letter of recommendation that Milgram had written. But despite looking through every box in his basement and garage, Keith couldn’t find it.

Finally, after much sleuthing on Keith’s part, the letter finally surfaced with another family member in another state – too late for my book – but it bears out what my research had established.

As you can see, although the letter falls short of acknowledging that Milgram could never have done it without Williams, Milgram clearly acknowledges Williams’ central role in the success of his experiments.