It’s half a century ago this year since Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments first made their way into print.

His first article about the experiments was published in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. But getting this first article into print wasn’t easy. Milgram had already had the article rejected by two other journal editors before it was finally accepted.

One editor sent back the article with a letter explaining that he’d rejected it because although Milgram’s results seemed shocking, Milgram hadn’t been able to explain them. ‘The psychological processes leading up to the obedient act remain a mystery,’ the editor concluded. And he had a point. In fact, it’s a criticism that has dogged Milgram’s research ever since.

But undaunted, Milgram resubmitted the article and it appeared in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology in 1963. He called the paper ‘Behavioral Study of Obedience’.

The abstract of the article reads as objective, impartial and cold. Milgram, writing in the style expected of an academic journal, wrote about his experiment and the suffering of the people involved in a deliberately impersonal tone.

The abstract of the article reads as objective, impartial and cold. Milgram, writing in the style expected of an academic journal, wrote about his experiment and the suffering of the people involved in a deliberately impersonal tone.

He used the passive voice which has the effect of de-emphasising the actions of the scientist behind the research and encouraging readers to believe that the people behind the research were invisible, impartial observers who merely set the stage and let the behaviour under investigation unfold.

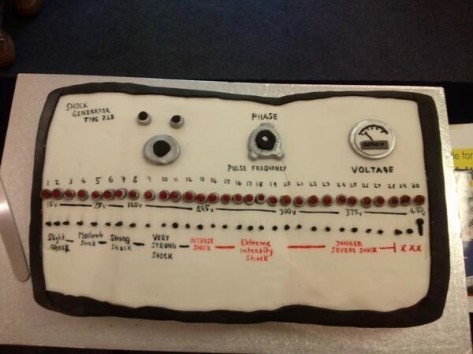

But we know from Milgram’s papers and recordings in the archives at Yale that this was far from the case. Stanley Milgram was far more stage manager than scientist – writing scripts, training actors, perfecting props and aiming for particular results.

The people being studied were depersonalised in this first journal abstract too. Milgram’s volunteers were simply and collectively referred to by the letter S. Their individual identities had vanished.

It’s likely that this seeming objectivity and dispassionate description of his subjects’ suffering is what got critics like Diana Baumrind so riled up about Milgram’s research and what she saw as his unethical treatment of the people involved. But for others his impersonal style was evidence of his objectivity and scientific integrity.

Whatever your point of view about the ethics, value or meaning of Milgram’s research there’s one thing that’s not in doubt. The obedience experiments have become the most famous psychological research of the twentieth century. But whether we’ll still be talking about them in 50 years time is anybody’s guess.

Photo of shock machine birthday cake courtesy of Durham School, UK.

Comments are closed.