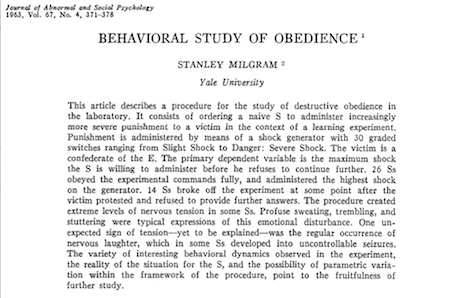

Here it is, the article that started it all, published 50 years ago in October 1963 – Stanley Milgram’s Behavioral Study of Obedience. But publication of this article hadn’t come easily for Stanley Milgram. It was rejected twice before the Journal of Abnormal Psychology accepted it for publication late in 1963.

Milgram writing as objective scientist

As was the convention in scientific writing, Milgram wrote in the passive voice, de-emphasising his own presence or role in the research. The procedure is ‘described’, the naïve S is ‘ordered’, but the describer and the one giving orders are absent, seeming to have no influence or control over the outcome. This device creates an impression of the scientist as impartial, a mere observer of what took place, rather than an active participant. You get the impression that Milgram merely set the stage and let the behaviour under study unfold.

Word choices shock

His choice of words in this abstract are revealing. Milgram’s volunteers – the people being studied – are simply and collectively referred to by the letter S. Again, this was common practise at the time. The ‘naïve’ S – a term generally used to mean unknowing, with connotations of being credulous, unsophisticated or simple – is ordered to give increasingly ‘severe punishment’ to a ‘victim’. Milgram leaves the reader to absorb these rather disturbing facts without letting us in on the experiment’s secret. The reader learns with growing fascination and repulsion that the punishment took the form of electric shocks and that Ss were ‘willing’ in their administration of punishment.

There’s something chilling about the juxtaposition of the ‘profusely sweating, trembling, and stuttering’ subjects with the distant tone of the language. The description of subjects’ responses in such clinical terms as ‘interesting behavioral dynamics’ and the ‘fruitfulness of further study’ reinforces Milgram’s objectivity and status as scientific observer.

What Milgram doesn’t mention in the first obedience article

What’s interesting about this abstract is what is does not tell us. Milgram does not tell us that the machine did not deliver shocks, that the victim felt no pain, that the experimenter was an actor. He withholds information until the body of the article, as a journalist might in order to incite curiosity and hook a reader into a story.

In the abstract of the article Milgram writes that the ‘victim protested and refused to provide further answers’. So it’s surprising to find later in the article, that the ‘victim’ did not make any sound at all until 300 volts when he banged on the wall. That is, the ‘teacher’ heard nothing at all from the learner until he had flicked 20 switches. (The learner didn’t give verbal answers to the ‘memory test’ but instead flicked a switch which lit up his answer in a light box on top of the shock machine).

When the learner did finally make a noise it wasn’t a shout, a complaint or a protest. In fact he didn’t speak at all. But you only realise this if you bother to read the rest of the article. If all you read was the abstract, you could be forgiven for thinking that the ‘teacher’ had continued to give shocks in the face of escalating cries and protests from the ‘victim.’

No wonder when it hit the newspaper headlines in November of the same year, Milgram’s experiment and its seemingly shocking results created a sensation.

Comments are closed.