How did Muzafer Sherif come to be studying warring groups of boys in 1950s America? Answering that question took me on a research journey back to the the final days of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Turkish Republic.

A Turkish Robbers Cave

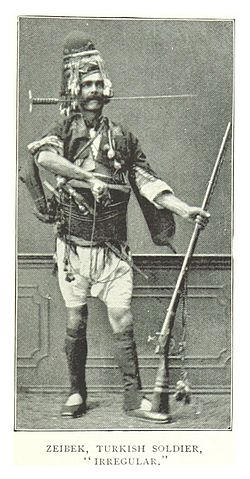

The mountain village of Bozdag where Sherif was born in 1906 had its own Robbers Cave. The mountain range provided lots of hiding places for zeybeks or bandits who roved in packs, robbing, kidnapping and demanding protection money from unwary travellers. During the nineteenth and early twentieth century the Ottoman government made repeated attempts to establish law and order and rein the outlaws in but without success. Whether local people regarded zeybeks as villains or heroes depended on whether they were victims or beneficiaries of their activities.

Villains to heroes

After the War of Independence, when tribes of zeybecks joined forces with Mustafa Kemal’s army to drive out the Greek troops the public reputation of the bandit tribes improved dramatically. Many became heroes of the new Republic, marching with Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) at the head of parades, receiving military rank and pensions for their services, their exploits celebrated in ballads and song.

You need look no further than the main street of Bozdag for a clue to the inspiration for the Robbers Cave experiment. At the centre of the village where Sherif was born a statue of bandit Poslu Mestan Efe now stands as a memorial to his role and that of his tribe in sparking the guerilla war that won Turkey its independence. From villain to hero, from outcast to insider, Sherif’s experiment might have occurred in 1950s America but it had its roots firmly in Ottoman Turkey.

Read more about The Lost Boys.

Comments are closed.